Introduction

This toolkit was put together alongside a review and redraft of the Devon SCP Child Neglect Strategy and has been developed for anyone working or volunteering with children, young people and families can get a better understanding of spotting, assessing, and dealing with childhood neglect. While it’s not an exhaustive list, it’s meant to be used alongside your professional judgment and as part of the some handy Neglect Quick Guides for reference.

This toolkit has been developed to share a range of multi-agency tools to support you in your direct work with children and families. As new resources are developed or suggested, we will add them to this toolkit, so we recommend that you check in regularly to review what’s available. If you have any neglect focused resources you think would be useful for others in a multi-agency context, we’d love to hear from you – please email us on

For everyone to work well together, agencies need to be on the same page about what neglect is and know the best ways to make positive changes to keep children and young people safe.

Understanding neglect:

Our understanding of neglect is also often rooted in our individual experiences and perceptions, such as our:

- experiences of being parented;

- experiences of being a parent;

- professional training;

- personal and professional experiences;

- awareness and recognition of inequalities and poverty; and

- cultural biases

Our perceptions of neglect can make it difficult to classify concerns, and often create obstacles for practitioners identifying neglect at the earliest point possible. This means it is more difficult to get the right support to families and address issues before they escalate and become critical, as emphasised in the final report of the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care. (MacAlister, 2022)

This guidance is to help with the above, and also intended to promote and assist good multi-agency work, so that all professionals can play an effective role in improving outcomes for children and young people.

Key principles of good practice

- Focus on the Child: Consider how the child’s circumstances impact them.

- Holistic View: Look at the child’s overall situation, including health, development, family, and environment.

- Parental Factors: Recognise various factors that can affect a parent’s ability to care for their child including parent capacity versus capacity to change.

- Strengths and Risks: Build on family strengths while addressing any difficulties or risks.

- Balanced Approach: Avoid being overly optimistic; balance strengths with potential risks, especially if care quality varies.

- Use Information: Utilise all available information sources, like agency files and the family’s network. When work together across organisational boundaries, sharing and processing concerns or worries about children who are being neglected in a clear and systematic way is crucial.

- Creative Engagement: Be innovative in working with the family, using different resources and techniques.

- Clear Expectations: Be specific about the changes needed and the timelines for achieving them alongside high expectations for all families.

- Recording: Keep accurate multi-agency chronologies to help you and other practitioners understand a child’s circumstance over time. Document events and concerns, building a comprehensive picture. Monitor or identify patterns in a child’s care or lack of care and recognise the cumulative impact of behaviours, patterns and experiences on the child.

- Review Opportunities: Regularly review progress with the multi-agency group, especially if changes aren’t happening as expected or if there are differing views.

- Professional Curiosity: Look for all signs of abuse or neglect and explore indicators. Learn about the child’s routines, thoughts, feelings and family relationships. Maintain a curious and open-minded attitude about the child’s life. Be alert to signs of abuse or neglect even during unrelated interactions with the family.

Understanding Neglect

- Persistent and Cumulative: Neglect usually happens over time and can be ongoing without a major event. Its effects can harm a child’s development.

- Chronic Condition: Small, seemingly insignificant events need to be looked at together to understand the full impact of neglect. There is a danger of viewing neglect as a chronic phenomenon as this involves waiting for a time when chronic issues are deemed to be present, which delays professional response to children’s safeguarding needs

- Professional Response: Waiting for chronic issues to be obvious can delay necessary actions to protect children. Pinpoint identification of causal factors – ‘treat the root not the symptom’

- One-Off Events: Neglect can also happen as a single incident, like during a family crisis or when a parent is under the influence of substances.

- Pattern Recognition: Even single incidents should be assessed to see if they are part of a larger pattern of neglect.

The definition of neglect in Working Together, 2023, refers to failure to undertake important parenting tasks which causes harm. These are often referred to as acts of omission and commission:

- Acts of Omission: These involve failing to do something that should have been done. For example, not providing necessary care or supervision for a child

- Acts of Commission: These involve actively doing something that causes harm. For example, intentionally leaving a child with an unsuitable caregiver

Both types of acts can have significant impacts on a child’s wellbeing and are important to consider when assessing neglect or abuse.

Neglect is often passive and involves not doing important parenting tasks (acts of omission). Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between not doing something (omission) and doing something harmful (commission) and both can happen at the same time. For example, leaving a child with an unsuitable person involves both not providing proper supervision (omission) and leaving the child with someone unsuitable (commission).

The key is to see which of the child’s needs are not being met, rather than why the parent is neglecting them. Even if neglect is passive it is still harmful to the child.

Neglect is less about understanding intent and more about assessing which of the child’s needs are not being met. Neglect may be passive, but it is nevertheless harmful.

Neglect often co-exists with other forms of abuse – emotional abuse is a key part of neglect. Physical abuse, sexual abuse, exposure to domestic abuse and child sexual exploitation can also occur with neglect. The presence of neglect should prompt anyone working or volunteering with children and young people to check for other types of neglect.

Parents and carers with complex and multiple needs – parents of neglected children often face issues like poor housing, poverty, lack of knowledge about children’s needs, disability, learning impairments and refugee status alongside multiple adversities such as parental substance/alcohol misuse, domestic abuse and mental health difficulties.

Forms and types of Neglect

The use of a shared framework is crucial to provide a common approach to help us make better decisions and evaluate child neglect. The Child Neglect Strategy outlines four forms of neglect which you can use to consider thresholds to prevent and intervene:

- Emotional Neglect: Ranges from ignoring the child to complete rejection. Children feel worthless and are treated with high criticism and low warmth.

- Disorganised Neglect: Inconsistent or chaotic parenting. The parent’s feelings dominate, leading to constant change and disruption.

- Depressed or Passive Neglect: The parent is withdrawn or has severe mental illness, focusing more on themselves than the child. They fail to meet the child’s needs and seem passive and helpless.

- Severe Deprivation Neglect: The child is left in extremely poor conditions, deprived of love and care, and may become ‘feral’ and roam the streets.

Each type of neglect affects children and parents differently and requires specific interventions.

The value of Reflective Discussion

- Reflective Discussion: Helps us understand child neglect better by examining our thoughts and biases.

- Shared Understanding: Reflection is key to achieving common views and consistent, shared high expectations of basic need – this can be done in peer, team, or organisational supervision.

- Articulate Thoughts: These discussions help professionals express and support their thoughts, observations, and intuitions, revealing personal biases.

- Self-Reflection: Provides opportunities to question our knowledge, prejudices, and norms.

- Inter-Professional Practice: Working together across different agencies is challenging due to varying roles, funding, language, and understandings. Supervision can build capacity and encourage co-production of plans.

- Clear Communication: It’s crucial to process concerns about neglected children systematically when working with our multi-agency partners across organisational boundaries.

Types of Neglect

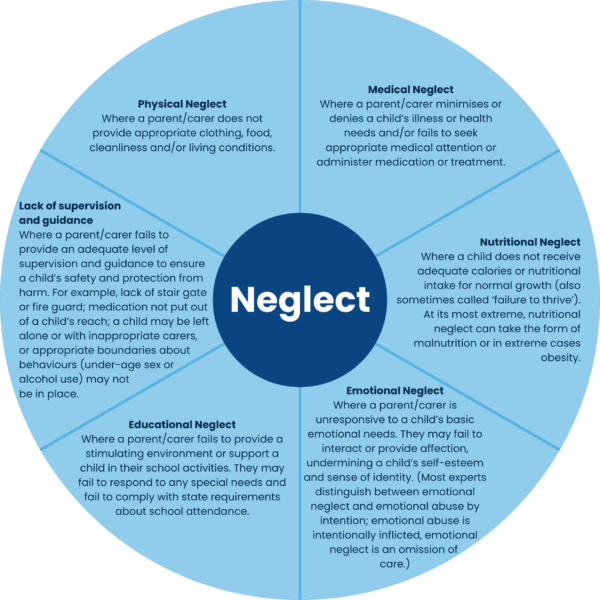

further to Howe’s four forms of neglect, neglect can also be categorized by way of the following types (Howarth 2007)

This wheel is helpful for practitioners to begin considering what type of neglect the child may be experiencing. It can assist in identifying and planning interventions in neglect and be useful when completing a chronology and/or planning the focus of an assessment.

Impact of Neglect

See our Neglect Quick Guides

Whilst the impact of neglect upon a child’s development is uniquely experienced by each child depending upon their individual circumstances, the nature of the neglect, and their degree of resilience, the persistent nature of neglect is corrosive and cumulative and can result in irreversible harm (Hildyard and Woolfe, 2002; Davies and Ward, 2011). The table below provides an overview of how neglect can manifest itself throughout childhood.

| Age | Impact of Neglect |

| 0-5 Years | – Failure to thrive; stunting, poor height and weight gain – Developmental delay; not meeting milestones e.g. not sitting, crawling, – Pale skin, poor hair and skin condition – Under-stimulation; head banging, rocking – Language delay – Emotional, social and behavioural difficulties e.g. frequent tantrums; persistent attending seeking or demanding; impulsivity or watchful and withdrawn – Frequent attendances at A&E – Persistent minor infections |

| 5-11 Years | – Poor concentration and achievement at school – Speech and language delay – Aggressive/withdrawn – Emotional, social and behavioural issues as above – Frequent attendances/admission to A&E – Isolated or struggles to make and keep friendships – Poor physical coordination/dexterity – Is bullied or bullies others |

| 11-18 Years | – Failure to learn – Poor motivation – Socially isolated/poor peer relationships – Increasingly high risk anti-social behaviour – Risk of CSE – Potential for self-harm/substance use – Feelings of low self-worth and alienation – Poor self-esteem and confidence |

Assessing the risks alongside protective factors and strengths

The assessment of risks and strengths in parenting requires a holistic, multi-agency assessment using professional judgement. The table below indicates some of the risk and protective factors to support such professional judgement. Where neglect is suspected, the list can be used as a tool to help assess whether the child is exposed to an elevated level of risk. This list is neither exhaustive nor listed in order of importance:

| Elevating Risk Factors | Strengths and protective factors |

| Basic needs of the child are not adequately met | Support network / extended family meet child’s needs. Parent or carer works meaningfully and in partnership to address shortfalls in parenting capacity |

| Substance misuse by parent / carer | Substance misuse is ‘controlled’; presence of another ‘good enough’ carer |

| Dysfunctional parent-child relationship Lack of affection to child Lack of attention and stimulation to child | Good attachment. Parent-child relationship is Strong |

| Mental health difficulties for parent/carer Parent/carer learning difficulties | Capacity and motivation for change; capacity to sustain change. Support available to minimise risks. Presence of another ‘good enough’ parent or carer |

| Low maternal self-esteem | Mother has positive view of self. Capacity and motivation for change |

| Existence of Domestic Abuse | Recognition and change in previous patterns of domestic abuse and sustaining this change |

| Age of parent or carer Support for parent/carer in parenting task | Parent/carer co-operation with provision of support services; maturity of parent/carer |

| Negative, adverse or abusive childhood experiences of parent/carer | Positive childhood. Understanding of own history of childhood adversity; motivation to parent more positively |

| History of abusive parenting | Abuse addressed in treatment |

| Child left home alone | Appropriate awareness of a child’s needs. Age appropriate activities and responsibilities provided |

| Failure to seek appropriate medical attention | Evidence of parent engaging positively with agency network (health) to meet the needs of the child |

Neglect in early years

There is a significant amount of research available detailing the impact of neglect in the formative years. Experiences during the first few years of life – positive and negative – shape the architecture of the developing brain. In young children, the impact of neglect may result in delayed or declining development and/or cognitive function; speech and language delay and insecure attachment. Research cited in Brandon et al (2014) states that neglect in the early years can be the most damaging form of abuse in terms of long-term mental health or social functioning.

Neglect in adolescence

Neglect is not something that just happens to young children and is not only damaging in the early years. A recent study by the Children Society found that more than one in seven 14-15 year olds attending a mainstream school lived with an adult caregiver who neglected them in one or more ways. Neglect is often thought to become more complex to discern or identify as young people develop, enter adolescence, and reach maturity. For adolescents, the boundaries between neglect and maltreatment are often more problematic: e.g. when a young person is forced to leave home through abuse (‘act of commission’) and find themselves ‘neglected’, hungry, and homeless. However, research commissioned by the Government in 2009 found important insights into both the effects in teenage years of early neglect and the factors associated with the onset of neglect during teenage years. Research has found that as young people get older they are less likely to receive a child protection response from Children’s Social Care. A variety of other responses were being used to meet young people’s needs, such as Child in Need or the Common Assessment Framework. Little is known about which approach works best for young people.

Assessment of Neglect

- Ongoing Process: Assessment isn’t a one-time event; it’s an ongoing process that considers the child’s family and community context.

- Understanding Impact: It’s crucial to understand how neglectful care affects the child and to assess the parents’ ability to address these issues with support.

- Focus on the Child: Sometimes, professionals get distracted by the parents’ welfare, but it’s essential to keep the child’s experience at the forefront.

- Serious Case Reviews: Many reviews have shown that practitioners often lower their standards while trying to support the family, which can be problematic.

- Clear Communication: Practitioners need to clearly outline unacceptable care aspects and help parents, family, friends, and community understand the child’s experience.

- Building Understanding: Even if the message is tough, delivering it effectively helps the family understand and address the issues in their planning.

By keeping these points in mind, we can better support children and families in addressing neglect.

Assessments should be:

- Holistic

- Child centred

- Use plain English

- Multi-agency

- Be informed by multiple sources of information and methods

- Use professional judgement

- Include strengths and risks in parenting

- Include family histories and patterns

- Focus on causes not symptoms

Factors in parents/carers

- History of physical and/or sexual abuse or neglect in own childhood; history of care

- Multiple losses – bereavements, abandonment, relationship/family breakdown

- Multiple pregnancies, with many losses – history of miscarriage and/or stillbirths

- Economic disadvantage/long term unemployment

- Parents with a mental health difficulty, including (post-natal) depression

- Parents with a learning difficulty/disability

- Parents with chronic ill health

- Domestic abuse in the household

- Parents with substance (drugs and alcohol) misuse

- Early parenthood

- Families headed by a lone parent or where there are transient partners

- Criminal convictions

- Strong ambivalence/hostility to helping organisations

Factors in the child

- Birth difficulties/prematurity

- Children with a disability/learning difficulty/complex needs

- Children living in large family with poor networks of support

- Children in larger families with siblings close in age

Environmental factors

- Families experience of racism/discrimination

- Family isolated/in dispute with neighbours

- Social disadvantage

- Multiple house moves/homelessness

- Poverty

Parental factors

Substance Misuse

If parents or carers misuse either drugs or alcohol and this use is chaotic, there is a strong likelihood that the needs of the child will be compromised. Any concerns of substance misuse need to be assessed thoroughly and the household carefully checked for dangers and risk of immediate harm. Parental addiction to substances including alcohol can alter capacity to prioritize the child’s needs over their own and in some cases alters parenting behaviour so that the child experiences inconsistent care, hostility, or has their needs ignored.

It is essential that there is a collaborative and joined-up approach between those working with adults involved in substance misuse and the Safeguarding Children Professionals so that there is a clear understanding regarding:

- The level and type of substance misuse, prognosis for change, commitment to reduce or control substance use.

- Whether the findings of any assessments are based on self-reporting or have been verified. It is essential that self-reports of reduction or cessation of substance misuse are verified before safeguarding activities are reduced. It is not effective safeguarding practice to take self-reports about substance addiction at face value.

- The impact that parental substance misuse is likely to have on parenting capacity, and the likelihood of the child receiving consistently good care under these circumstances. Parental drug use can and does cause serious harm to children of every age. Reducing the harm to children should be the main objective of drug policy and practice.

- Effective treatment of the parent can have major benefits to the child.

- By working together, services can take practical steps to protect and improve the health and wellbeing of affected children.

- The number of affected children is only likely to decrease when the level of problematic parental substance use decreases.

- Whenever substance misuse is identified as a concern, a thorough assessment of the impact upon parenting and potential implications for the child must be completed.

Questions to consider:

- What is the carer’s frequency of substance misues and what substance are they using?

- Does the carer believe it is normal for children to be exposed to regular alcohol/substance misuse?

- Does the carer understand the importance of hygiene, emotional and physical care of their children and arrange for additional support when unable to fully provide for the child?

- Are finances affected by parental substance/alcohol misuse?

- Is the mood of the carer irritable or distance at times?

- Are alcohol and/or drugs stored safely?

- Is the carer aware of the impact of substance misuse on the child (including unborn child)?

- Does the carer hold the child responsible for their use and blame their continual use on the child?

Mental Health Difficulties

It is known that mental health problems in parents and carers can significantly impact upon parenting capacity. Type of mental illness and individual circumstances are factors that need to be considered in any assessments. Possible contributory factors when assessing neglect:

- Severe depression or psychotic illness impacting upon the ability to interact with or stimulate a young child and/or provide consistent parenting.

- Delusional beliefs about a child, or being shared with the child, to the extent that the child’s development and/or health are compromised.

- Specialist advice about the impact of mental health difficulties on parenting capacity must always be sought from an appropriate mental health practitioner in these cases. It is essential that there is a collaborative and joined-up approach between those working with adults who have mental health difficulties and the safeguarding children professionals so that there is a clear understanding between both sets of staff about:

- The degree and manifestation of the mental health difficulty, treatment plan, and prognosis.

- The implications for parenting capacity and good care being offered to the child consistently in relation to mental health difficulty. For parents and carers where their own issues can impact on their ability to care for their children (e.g. mental ill health, substance misuse) plans with the family in advance of a crisis should take place.

- Family, friends, and community should be invited to plan together and develop strategies that provide effective support day to day and during periods of crisis e.g. identifying a safe family member who will care for the child/ren when the parent has a period of ill health and is not able to care for them.

- Assumptions that periods of crisis may occur should be made and contingency plans developed in advance of the next episode or crisis.

- Enabling and facilitating families to find their own solutions will result in owned and sustained support for the children. This does not negate the need for families to be able to access the appropriate professional support when required.

Questions to consider:

- Does the carer have a history of depression or is currently experiencing depression?

- Does the carer talk about feelings of depression/low mood in front of the children?

- Are the child’s needs understood, and the carer is aware of the impact of talking

- about their mental health issues in front of the children?

- Does the carer hold the child responsible for feelings of depression and is open with

- the child and /or other about this?

- Is the carer hostile when given advice focused on stopping this behaviour and carer does not recognise the impact on the child

If a parent/carer is motivated to access support for their mental health, we know from research that it reduces likelihood of harm occurring for a child.

Learning Disabilities/Difficulties

The use of the terms learning disability and learning difficulty are often interchangeable. A learning disability is described as a reduced intellectual ability and difficulty with everyday activities – for example household tasks, socializing, or managing money, which affects someone for their whole life. A learning difficulty is any learning or emotional problem that affects, or substantially affects, a person’s ability to learn, get along with others, and follow convention. Many parents and carers with a learning disability have an instinct to parent their child well, whilst others may not. However, even with a good caring instinct, parents and carers with a learning disability may have difficulty in acquiring the skills to care (e.g. feeding, bathing, cleaning, and stimulating) or be able to adapt to their child’s developing needs. The degree of the learning disability/difficulty as well as their commitment and capacity to undertake the parenting task are key areas to assess. It is a priority that the child’s health and development needs are met both now and as those needs change in the future; and that the child is not exposed to harm as a result of parenting, which deprives them of having their physical

Questions to consider:

- Is it apparent that the carer has any learning disability? And if so, have we determined what help will be needed to support the carer’s understanding and involvement?

- What is the level of understanding of the carer?

- Does the carer understand written advice and/or instruction?

- What adaptations can be made to support the carer’s understanding of this plan? Who can support with developing individualized resources when this is needed?

Domestic abuse

Growing up in a violent and threatening environment can significantly impair the health and development of children, as well as expose them to ongoing risk of physical harm. Chronic, unresolved disputes between adults, whether they involve violence or not, have an adverse impact on the child’s emotional wellbeing, making emotional neglect a relevant concern. Professionals need to remain alert to the indicators of neglect whenever domestic abuse is raised as an issue and equally consider whether the child is exposed to domestic abuse when working with cases of neglect.

Questions to consider:

- Is a parent/carer currently experiencing harm that the child is not protected from?

- Does the parent/carer argue aggressively and/or is physically abusive?

- Does the parent/carer understand the impact of arguments and anger on children and is sensitive to this?

Professional challenge

Common professional challenges

- The family don’t understand what the problems are

- There is a plan but there are still concerns for a child’s safety

- The plan doesn’t seem to be working

- The family know what good parenting is but don’t do it consistently

These issues are not unusual in our work with families. If any of these appear to be the case, they represent an opportunity to stop and review together. Sometimes it can be really helpful to have someone external to the team around the family to support reflection and help find a way forward.

Use of safeguarding supervision

The document Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023) Working together to safeguard children 2023: statutory guidance outlines the requirement for accessing safeguarding children supervision. Effective safeguarding supervision is essential for practitioners working with children and families, keeping children safe is challenging and evokes strong emotions such as upset, shock, or anger. Over time, these emotions can impact their general wellbeing. Reflective supervision helps practitioners manage the challenging and emotional demands of the work, leading to safer practice and better decision-making. Reflective supervision allows practitioners to critically analyse their work, manage complex situations, and focus on the welfare of children. This approach supports staff in developing critical thinking skills which are essential for safe practice and better decision-making.

Safeguarding supervision provides a safe space for staff to reflect on their practice, explore concerns about children’s welfare, and experience professional challenge. It fosters a culture of mutual support, teamwork, and continuous improvement. Effective supervision is linked to better staff retention and development, as it supports practitioners in coping with the emotional demands of their work.

Informal or “corridor conversations” in supervision can pose significant risks if not properly documented. These informal discussions may go unrecorded, leading to gaps in communication and care. Serious case reviews have shown that such conversations can significantly influence the direction of work with a child or their family, sometimes with serious consequences. Therefore, it is crucial that all supervisory conversations, whether formal or informal, are appropriately documented to maintain a high standard of care and accountability.

It is important that practitioners seek safeguarding supervision from their agency’s safeguarding lead or safeguarding team when there are concerns about neglect. Safeguarding supervision provides a vital opportunity for support, challenge, and learning around complex safeguarding cases.

When working with families where neglect is a concern, there are the following considerations:

- Emotional Impact: In case of serious neglect practitioners may experience anxiety and despair when working with challenging family situations. Supervision should identify these feelings and help to address these emotions.

- Focus and Purpose: Effective supervision must provide direction and purpose, regularly reviewing the children’s situation and assessing risks holistically This prevents lack of direction and drift which are common characteristics in several cases which have resulted in tragic outcomes.

- Realistic Timeframes: Case closure in serious neglect situations is often unrealistic within typical timeframes. Supervision should discuss desired outcomes for the child.

- Collaboration: Inter-agency and inter-professional collaboration is crucial. Supervision can include managers and workers from other agencies when necessary.

- Transparency with Parents: Practitioners should be open and honest with parents about how their care can be improved to meet their children’s needs, focusing on immediate safety and healthy development.

- Identifying Challenges: Supervision should clearly identify where partnership efforts are failing and may require long-term agency involvement with a clear purpose and support for parents.

- Professional Development: For practitioners, effective supervision can be a powerful tool for fostering continuous learning and self-improvement, highlighting area

- Reflection: Supervision should always promote honest and meaningful reflection.

Roles and responsibilities

All agencies, whether statutory or voluntary, have a duty to:

- Share information about children at risk of harm from neglect.

- Contribute to the assessment process.

- Lead the assessment and multi-agency meetings when appropriate.

All practitioners should recognise signs of neglect and act quickly to provide support at the earliest opportunity.

General Practitioners (GPs)

GP surgeries are well placed and have a key role in responding to incidents of neglect. GP surgeries can be involved with families over a long period of time, potentially providing a longitudinal view of the family which could allow early intervention when there are concerns about the maltreatment and neglect of children. GPs can serve as a helpful source of information about a child/ren which can be used to form a cumulative view of the health and wellbeing of the child/ren and family. GPs can contribute to the team around the child approach at the earliest stage of help to support the family and their network of support to address concerns before they have any chance to escalate.

Paediatricians

Paediatricians are well placed to respond to instances of childhood neglect in the health economy. Paediatricians will have an understanding of the assessment of risk and harm; they will also have a clear understanding of the effects of parental behaviour on children and young people and will have a role in inter-agency responses to cases of neglect. Paediatricians are also able to identify associated medical conditions, mental health problems, and other issues that may affect the health and wellbeing of children. Paediatricians are also able to contribute to the work of multi-agency teams where there are child protection concerns.

Midwives

Midwives have a key role in identifying neglect at the earliest opportunity. In seeing parents during the ante-natal period, they are best placed to work in partnership with parents and carers and work with other universal and targeted service providers to support an early help offer prior to any risk of escalating concerns.

Health Visitors

Health visitors are amongst the first professionals to see a child within the family home. As a result, health visitors are best placed to identify vulnerable families, provide, deliver, and coordinate evidence-based packages of additional care, including maternal mental health and wellbeing, parenting issues, families at risk of poor outcomes, and children with additional health needs. Health visitors will identify concerns at an early stage and work with other universal and targeted service providers alongside the family to support an early help offer prior to any risk of escalating concerns. They will consider early help solutions via the Early Help Assessment tool and team around the family (TAF) approach. They can act as the lead professional with families to help coordinate this approach.

Dentists

Dentists are a universal service provider well placed to identify the indicators of physical neglect when children attend for emergency treatment. These are children who may not attend for routine dental check-ups. They can liaise with other key professionals such as GPs, schools, and school nurses to consider their concerns further.

School Nurses

Through their work in schools, school nurses are well placed to identify children and young people who may be at risk and to act to safeguard their welfare. School nurses will identify concerns at an early stage and work with other universal and targeted service providers alongside the family to support an early help offer prior to any risk of escalating concerns. They will consider early help solutions via the early help assessment framework and team around the family (TAF) approach. They can act as the lead professional with families to help coordinate this approach.

The Role of Early Years and Education

Early years providers such as nurseries and children’s centres and schools and educational institutions are well-placed to support children and families where there are concerns regarding neglect. They are in a position to identify concerns early, preventing concerns from escalating and ensuring that children get the help and support that they need. Detailed guidance for school and college staff will be provided in Keeping children safe in education 2024 and EYFS statutory framework for childminders, EYFS statutory framework for group and school-based providers. All professionals in universal and targeted services, who have concerns about children must ensure that they offer early help. They will complete a request for early help.

Police

Police have a key role in identification of neglect through contact with children and families under circumstances that legitimately allow them access to homes and private lives, often concealed from other professionals. Police must be aware of the indicators and be professionally curious to identify the existence and extent of neglect, conduct a dynamic risk assessment, and take proportionate action. Under section 46 of the Children Act 1989, where a police officer has reasonable cause to believe that a child would otherwise be likely to suffer significant harm, the officer may use their Police Protection Powers to remove the child to suitable accommodation and keep them there, or take reasonable steps to ensure that the child’s removal from any hospital or other place in which the child is then being accommodated is prevented. Whether Police Protection Powers are invoked, or whether the identified neglect does not warrant immediate safeguarding action, it is the responsibility of the Police to then notify other relevant agencies through either the multi-agency MASH or internal ViST (Vulnerability indicator Screening Tool) processes and inform a multi-agency risk assessment, based on all relevant information.

Fire and Ambulance Services

Fire and Ambulance Services are uniquely placed to identify neglectful circumstances including home conditions when responding to emergencies. It is important that they record their concerns and report these formally whenever required. This information helps to build a full picture of the circumstances that children are living in. This evidence supports holistic assessment and child protection.

Children’s Social Work

Children’s Social Workers become involved with families where concerns have escalated to a level where a child has suffered significant harm or is likely to suffer continuing significant harm. In most cases where neglect is a cause for concern, an early help approach via universal, single agency or multi-agency colleagues will have been offered to the family via a team around the family approach (TAF) to support them to make the changes required to ensure their children’s safety. The evidence for serious neglect is most often based on cumulative harm, rather than from single incidents. It is this cumulative evidence which combines to support a consideration of threshold for significant harm. Therefore, Children’s Social Work Services must have an evidenced-based understanding about this from all professionals involved in order to build an accurate picture of risk. It is this evidence that will shape a plan to reduce harm and further risk of continuing harm; ideally in partnership with families.

The Role of Housing

The housing department may have information about families, identify cases of neglect, or contribute information to assessments. The housing department has a critical role to play in cases of poor home conditions, social isolation, and domestic abuse. Staff have an important role to play in reporting concerns where they believe that a family may benefit from extra support or a child may be in need of protection.

The Role of Adult Facing Services

All adult facing services have important information about families and a role to play in identifying cases of neglect and/or contributing information to assessments. Through work with parents, they may become aware of families who may benefit from support and/or children who are at risk of/experiencing neglect. Practitioners have a responsibility to be aware of signs of child neglect and refer to appropriate service. Staff will work in collaboration with other agencies in contributing to assessments and will follow all relevant child protection policies, procedures, and protocols.

Legal framework

Emergency Protection Order (EPO)

Under Section 44 of the Children Act 1989, the local authority, the NSPCC, a police officer, or any other person can apply for an Emergency Protection Order (EPO) where there is risk of significant harm to a child. Under the Order, the local authority acquires Parental Responsibility for the child. In practice, local authorities will make most applications. The local authority must initiate a Section 47 Enquiry when a child has been made the subject of an EPO. An EPO lasts 8 days and can be extended for a further 7.

Police Protection Powers (PPP)

Under section 46 of the Children Act 1989, where a Police Constable has reasonable cause to believe that a child would otherwise be likely to suffer Significant Harm, the child may be kept in or removed to suitable accommodation where they may be protected, e.g., a relative’s home, a hospital, a Police Station, a Foster Home, Children’s Home, or other suitable place. Police Protection Powers last 72 hours and should only be used in exceptional circumstances and where there is insufficient time to seek an Emergency Protection Order or other reasons prevail relating to the child’s immediate safety.

Section 20 Children Act 1989

Local Authority placement of a child in suitable alternative accommodation with the parent’s consent. This could be with a suitable family member or close friend.

- Parents must give valid consent to section 20 accommodation and their agreement must be ‘real’.

- The parents must understand what they are agreeing to – they must have ‘capacity’.

- The parents must have all the relevant information.

- Removing a child under section 20 must be fair and proportionate.

- Parents must be told they have a right to take legal advice.

- Parents must be told they have a right to withdraw their consent.

Care Order

A Care Order can be made in care proceedings brought under Section 31 of the Children Act 1989 if the threshold criteria is met. The order grants Parental Responsibility for the child to the local authority specified in the Order, to be shared with the parents. A Care Order lasts until the child is 18 unless discharged earlier.

Learning and development

The Devon SCP offers the following:

- Making Sense of Child Neglect (Group 3) – Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership – Group 3 refresher/special interest course specifically focused on neglect

- Tools to Assess Neglect (Graded Care Profile 2 Training) – Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership – an assessment tool that supports practitioners to make a judgement about whether or not parental care is neglectful.

- Tools to Assess Neglect Refresher – Embedding GCP2 into practice – Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership – a course to refresh your understanding of recognizing and responding to child neglect and poor parental care

- Podcast: recognising and responding to child neglect | NSPCC Learning – 2 part podcast series exploring neglect and what can be done to support children and families experiencing it including:

- what neglect is and some of the harder to spot signs of neglect

- the difficulties and challenges when conducting assessments

- issues and challenges that arise in relation to children’s age and stage; covering early years, adolescence and additional needs.

- what they’ve learnt from their experiences and what they find works when supporting families.

Further reading; evidence and research

Department for Education:

This link takes you to the safeguarding children pages of the website where there are numerous articles, reviews and research papers related to child neglect as well as wider safeguarding concerns

https://www.gov.uk/childrens-services/safeguarding-children

Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership:

The Partnership’s website The Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership (Devon SCP) has the link to the South West Child Protection Procedures (SWCPP) The Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership (Devon SCP) for identifying and responding to safeguarding concerns. The website also contains numerous articles, links and resources that can support practitioner and managers. This link takes you to the safeguarding children pages of the website where there are numerous articles, reviews and research papers related to child neglect as well as wider safeguarding concerns.

- Devon Levels of Need Tool – Levels of Need – Devon Safeguarding Children Partnership

- Devon SCP Professional Curiosity Guidance

- Devon SCP Case Resolution Protocol

- Information Sharing Guidance – May 2024 and Slides

NSPCC:

The website provides access to an information service to help to locate practice, policy and research on particular topics. CASPER provides free email updates about safeguarding matters and inform which includes full and summary research documents http://www.nspcc.org.uk

Helpful tools for practitioners

All of these tools are available on SharePoint.

Chronologies

- Cumulative Chronology of Neglect and its impact template

- Neglect Chronology template

- Chronologies quick guide

Genograms and Ecomaps

GCP2

Hoarding Guidance

Impact of Neglect Quick Guides

- Pre-birth

- 0-2 year olds

- 3-4 year olds

- 5-11 year olds

- 12-17 year olds

- Types of neglect, indicators and impact

Parents and Carers with Learning Disabilities

- Good practice guidance on working with parents with a learning disability

- Parents with Learning Disabilities – multi-agency policy

NICE Guidance

Other tools

- Home Conditions – Neglect Framework

- Neglect in Adolescence

- Education Neglect 7 point briefing (to be added soon)

- Neglect One Minute Guide (to be added soon)

- Three Houses toolkit (to be added soon)

- A day in the life

- Recognising and responding to cumulative harm

- The developing world of the child – seeing the child guidance

- Mother Object Relations Sales (MORS) – child and infant assessment guides

- SMART planning

- NSPCC Neglect Report – Too Little, Too Late

- Devon SCP Multi-agency Child Neglect Matters booklet (for practitioners, parents and children)

References

Brandon, M., et al. (2012). New Learning from Serious Case Reviews. DfE, London.

Brandon, M., et al. (2013). Neglect in Serious Case Reviews (2012-2013). UEA.

Gerhardt, S. (2004). Why Love Matters; How Affection Shapes the Baby’s Brain. Routledge, London.

Horwath, J. (2001). The Child’s World. Kingsley, London.

Horwath, J., & Morrison, T. (2001). Assessment of Parental Motivation to Change.